Journey with Jellies (including Octopus)

Journey with Jellies (including Giant Pacific Octopus)

This is one of the newer exhibits at The Maritime Aquarium. At times we station a Gallery Ambassador here when all of the other stations are filled.

Journey with Jellies

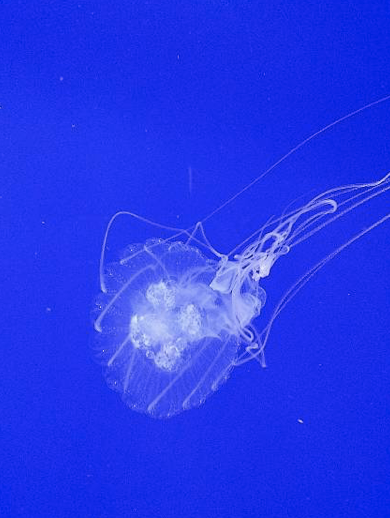

With “Journey with Jellies,” The Maritime Aquarium now displays the most jelly species in the region. Jellies have been among the most popular animals in The Maritime Aquarium for more than 20 years.

This bigger new space builds around the tall centerpiece display of moon jellies, and offers large new displays with such non-native species as Pacific sea nettles, upside-down jellies, blue blubber jellies, and more. Journey with Jellies” has traditional “window” displays of jellies, but also unique displays of jellies living in cascading globe and half-dome habitats.

Aquarium guests can learn about how jellies sting and about their unique life cycles. In addition to jellies, this new exhibit space also includes a big new natural habitat for the Aquarium’s giant Pacific octopus, as well as a new display featuring lionfish, a species with a large splay of venomous spines that are a troubling invasive presence on the Atlantic coast.

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini)

The giant Pacific octopus grows bigger and lives longer than any other octopus species. A specimen that was 30 feet across and weighed more than 600 pounds holds the size record. The average giant Pacific octopus reaches 16 feet across and weighs 110 lbs.

Along with eight arms, an octopus also has three hearts and nine brains. Two of the three hearts pump blood to the gills, while the third circulates blood to the rest of the body. Octopuses use one central brain to control their nervous systems and a small brain in each arm to control movement. Octopuses, including the giant Pacific octopus, are also known for having blue blood thanks to a copper-rich protein called hemocyanin in their bloodstream, which is efficient for oxygen transport in cold ocean environments.

We have one Giant Pacific Octopus exhibit – a 1,000 gallon tank in the Journey with Jellies gallery. They reach exhibit size in about 1 1/2 years.

Life Cycle

They typically live three to five years, with both males and females dying soon after breeding. After reproduction, they enter a stage called senescence, which involves obvious changes in behavior and appearance, including a reduced appetite, retraction of skin around the eyes giving them a more pronounced appearance, increased activity in uncoordinated patterns, and white lesions all over the body. While the duration of this stage is variable, it typically lasts about one to two months.

After mating, a female will lay up to 74,000 eggs or more in a deep den or cave and live there for seven months watching over them. During this time, dedicated mothers will not venture out for food, and shortly after the young hatch, the mother will die. Because of this behavior, it is difficult to know population numbers of the giant Pacific octopus.

Physiology & Camouflage

The mantle of the octopus is spherical in shape and contains most of the animal's major organs. By contracting or expanding tiny pigment-containing sacs within cells known as chromatophores, an octopus can change the color of its skin, giving it the ability to blend into the environment. Subcategories of chromatophores include iridophores (reflective platelets) and leucophores (refractive platelets.) Octopuses are also able to alter their skin texture, providing even better camouflage. Dermal muscles in the octopus's skin can create a heavily textured look through papillation, or cause skin to appear smooth. All of these abilities are under nervous system control.

Diet and Range

They hunt at night, surviving primarily on shrimp, clams, lobsters, and fish, but have also been known to attack and eat sharks as well as birds, using their sharp, beaklike mouths to puncture and tear flesh. They range throughout the temperate waters of the Pacific, from southern California to Alaska, west to the Aleutian Islands and Japan.

Intelligence and Population

Highly intelligent creatures, giant Pacific octopuses have learned to open jars, mimic other octopuses, and solve mazes in lab tests. Our aquarists have a challenge keeping the mind “active” on these intelligent invertebrates. A variety of enrichment activities are presented- including toys, puzzles, and live food items. Our aquarists have even trained our Octopuses to sit inside a laundry basket for vet checks and transportation.

Conservation Status

Their population numbers are unknown, and they do not currently appear on any lists of endangered or vulnerable animals. However, they are sensitive to environmental conditions and may be suffering from high pollution levels in their range.

Watch a keeper chat video with our Giant Pacific Octopus

Upside-down jelly (Cassiopea sp.)

Cassiopea andromeda - One of 8 species of the genus Cassipoea. They have a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae, a photosynthetic algae. Cassiopea lay upside down in areas with adequate penetration of sunlight for the algae to grow.

Color: The bell is yellow-brown with white streaks or spots.

Habitat: Shallow, tropical marine waters, swamps, mudflats, lagoons, mangroves.

Range: Warm coastal regions around the world.

Size: Up to 12 inches wide.

Diet: Carnivorous. They paralyze small sea animals with mucous and nematocysts.

Reproduction: Like other cnidarians, upside-down jellies have an alternation of generation. In the polyp form, they reproduce asexually through budding. In medusa form, reproduction is sexual. The male releases sperm in the water. The female medusa uses its tentacles to bring the sperm to fertilize the eggs it has produced.

Fun Fact: Upside-down jellies can deliver a painful sting to humans, resulting in rash and swelling.

Pacific sea nettle (Chrysaora fuscescens)

Geographic Distribution

Commonly in coastal waters of California and Oregon. Less common west to Japan, north to the Gulf of Alaska, and south to the Baja Peninsula.

Habitat

Pacific sea nettles live near the surface of the water column in shallow bays and harbors in the fall and winter. In spring and summer they often form large swarms in deep ocean waters.

Physical Characteristics

The bell, or medusa, of Pacific sea nettles is dish-shaped, with shallow scallops (lobes) around the margin. Twenty-four long, ribbon-like, thin tentacles stream from the bell’s margin and four long, lacy, pointed oral arms spiral out counterclockwise from the center of the bell. The bell is covered with warts that contain nematocysts (stinging cells).

The bell is yellowish or reddish-brown with a darker margin. There may be a lighter star pattern with 16 to 32 rays on the exumbrella, the outside surface of the bell. The tentacles and oral arms are very dark reddish to yellowish-brown in color.

Size

The bell diameter can be up to 30 cm (1 ft) with oral arms reaching as long as 1 m (3.3 ft). Oral arms can reach 3.6-4.6 m (12-15 ft). However, ton average, the sea nettles are are usually smaller.

Diet

These jellies are carnivores, feeding on other jellies and a variety of zooplankton including larval fishes and eggs, comb jellies, other jellies, and pelagic snails.. As they move through the water with both oral arms and tentacles extended, their tentacles stream below, above, and alongside the bell creating a large surface area with which to capture prey. When physical contact is made with a prey item, the nematocyst is triggered, causing the nematocyst cell to burst open. The cnidae explodes from the cell and discharges its toxin into the prey, paralyzing it. The trailing tentacles retract and transport the food up the tentacle to the gastric cavity where digestion occurs. Large prey is partially digested on the oral arms before being transported to the gastrovascular cavity. Once the prey has been transferred, the tentacles extend again to become fishing lines once more.

Reproduction

Sea nettles are broadcast spawners; they do not fertilize internally. The fertilized eggs hatch in the water column as round or oval ciliated larvae, the planulae. The planulae change to a pear shape in two to three hours, swimming freely for a time while searching for a shaded and rough area to which to attach their posterior ends to become stationary planocysts.

The planocysts go through an asexual reproductive process developing into tentacled polyps called scyphistomes. Either budding off of non-motile clone scyphistomes occurs or if environmental conditions are suitable, a procedure called strobilation begins. In strobilation, miniature medusa-like structures called strobilia are formed on a stalk, one on top of the other like a stack of dinner plates with the most mature on top. The strobilia bud off as individual ephyra (young jellies) that develop marginal lobes, sensory structures, tentacles, elaborate oral arms, and finally the bell shape of the adult male or female medusa, the form in which sexual reproduction occurs.

Behavior

When sea nettles ‘swim’ the shape of their bell changes markedly from the shape of an umbrella to flat as the bell contracts and expands due to action by its coronal (circular) and radial muscles. The coronal muscles act first, drawing the umbrella inward and downward. Then the radial muscles cause it to bend further. There is an initial backward thrust of the umbrella on the water, followed by an outward jet of water with each contraction. There is sufficient drag on the bell to virtually stop the jelly in the water at the end of recovery. The jelly then accelerates again during the next beat. In the resting state at the end of the “swimming” stroke, the jelly’s bell is flattened and the lobes give it the appearance of an eight-pointed star.

Adaptation

Sea nettles do not see images but are able to differentiate between light and dark using small pigmented structures on the bell or tentacle base called “eye spots” or ocelli. They maintain their balance and orientation to the ocean bottom and surface with statocysts, vesicles that contain mineral salts that stimulate sensory cells in response to the jelly’s movement

Longevity

These sea jellies have about six month’s life span with some living to one year of age. In protected environments such as aquariums they have lived for 18 months due to the absence of predators and availability of an adequate food supply.

Conservation

Many scientists believe that urban runoff and global climate change is changing the nutrient composition and temperature of coastal waters, causing an increase in swarms of sea jellies. As more jellies consume more larval fishes, fewer fish survive to become adults.

Atlantic sea nettle (Chrysaora quinquecirrha)

Geographic Distribution

Cape Cod south along the U.S. East Coast, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico. Larger numbers in Chesapeake Bay, unequaled elsewhere.

Habitat

These sea nettles are found in the high-salinity open ocean, the lower salinity of bays, and the brackish water of estuaries.

Physical Characteristics

The medusa (bell) of the Atlantic sea nettle is somewhat saucer-shaped. Four thick, long, lacy oral arms hang from the bell margin, which is scalloped into shallow lobe-like structures called lappets. There are 4 to 40 long thread-like tentacles on the bell margin that alternate with marginal sense lobes (rhopalia) between lobes. Pink nettles usually have 10 tentacles and white ones have 21. The manubrium extends well below the bell margin. The four gonads are heart-shaped. Radial canals are present.

Bell coloration varies by location. Jellies in the south part of Chesapeake Bay and the open ocean are pink to reddish-maroon with radiating red stripes that may extend down the yellow tentacles. Those in the low salinity waters of estuaries have a white bell and no radial stripes. Jellies found along the southeast coast outside of Chesapeake Bay have the same color variation. Gonads can be pink, light gray, yellow, or clear.

Size

Size varies by location. The jellies found in Chesapeake Bay’s middle bay and estuaries have a bell diameter of about 10 cm (4 in) and a height of 5 cm (2 in). Open ocean and outer bay jellies may have bell diameters of 13 to 25 cm (5 to 8 in) and heights of 13 to 19 cm (5 to 7 in).

Diet

Like other sea nettles, the Atlantic sea nettle is a voracious carnivore. Its preferred prey is ctenophores (comb jellies) in the genus Mnemiopsis. It also eats small fishes, copepods, young minnows, mosquito larvae, bay anchovy eggs, and other zooplankton.

Reproduction

This sea nettle becomes sexually mature when the bell diameter is about 3.81 cm (1.5 in) in diameter. An adult female produces eggs that are held in its oral arms around its mouth. The male jelly releases sperm into the water and the female uses her oral arms and tentacles to bring in sperm to fertilize her eggs. Eggs and sperm are shed daily from May to August in the Chesapeake Bay. A female that has a 10 cm (4 in) diameter bell will produce 40,000 eggs a day. The fertilized eggs remain on the oral arms until they develop into ciliated larvae, the planulae. At first they are round or oval-shaped, however, within two to three hours they change into a pear shape. Eventually they drop off the oral arms, swimming freely for a time while searching for a suitable substrate on which to attach, usually the bottom of a structure that is shaded and rough. In the bay, the underside of oyster shells is a preferred location. They attach upside-down with their tentacles pointing upward to filter feed. They are now known as sessile planocysts.

Depending upon environmental conditions, the planocysts go through one of two reproductive phases, either asexual or sexual. They either bud off non-motile clones of themselves or a phase called strobilation occurs. Strobilation only occurs when the water quality, temperature, and salinity are favorable and food supply is adequate. Miniature medusa-like structures called strobilia are formed on a stalk, one on top of the other like a stack of dinner plates with the most mature on top. The strobilia bud off as individual eyphyra that develop marginal lobes, rhopila, tentacles, elaborate oral arms, and finally, the bell shape of the adult medusa, the form in which sexual reproduction occurs. Each polyp produces up to 45 ephyrae per summer.

Behavior

Trailing tentacles sting and transport food up the central tentacle to the jelly’s gastrovascular cavity where digestion takes place. Nettles can and do feed constantly because their many tentacles can function independently of each other. As they trail they offer a large surface area with which to capture prey. Large prey are partially digested on the oral arms before being transported to the gastrovascular cavity.

This sea nettle has both coronal (circular) and radial muscles. As it swims, the shape of its bell changes markedly from flat to bell-shaped during extension and contraction of the bell. The coronal muscles act first, drawing the bell inward and downward. The radial muscles then cause the bell to bend diameter. There is an initial backward thrust of the bell on the water followed by an outward jet of water with each contraction. There is sufficient drag on the bell to virtually stop the jelly in the water at the end of recovery. The jelly then accelerates again during the next beat. In the resting state at the end of the swimming stroke, the jelly’s bell is flattened and the lobes give it the appearance of an eight-pointed star.

In the open ocean they have a symbiotic relationship with blue crabs that ride on the bell and clean off debris and parasites. Juvenile spider crabs live in the bell feeding on the jelly’s mucus and tissues. Harvest fish, Peprilus alepidotus, seek shelter in the tentacles. The nudibranchs, Cratena pilata, prey on the polyps, steal the most potent nematocysts and, without digesting them, store them in their cerata for their own later use as defensive tools.

Adaptation

Although the toxin is mild, the sting is painful and can cause severe reactions in people sensitive to its sting.

Most jellies prefer the high salinity of the ocean, which is 35ppt (35 parts salt to 1,000 parts water) as their habitat. The Atlantic sea nettle is unusual in that it has the ability to live in low-salinity water, making brackish estuaries a suitable seasonal habitat.

The timing and intensity of spring rains and the water temperature influence the number of Atlantic sea nettles in Chesapeake Bay. In a dry spring with warm water, ephyrae bud from the polyps that have “wintered” over. When heavy rain runoff into the estuaries decreases the salinity of the water to below a salinity of 10 ppt, fewer medusae enter the bay to reproduce and fewer polyps bud.

Longevity

The lifespan is about a year, however, when seasonal heavy rains reduce the water’s salinity to about 7 ppt, the planocysts remain dormant for as long as two years, extending the life expectancy from the polyp stage.

Conservation

The swarms of Atlantic sea nettles that appear in Chesapeake Bay during the late spring and summer months impact recreational beachgoers and boaters. Numbers can be so large that beaches are closed. Control methods have not been successful. Netting of the beaches has not proven effective because the jellies clog the nets, keeping out desirable fauna. Broadcasting of chemicals on the bay bottom in an effort to kill the polyps has killed desirable bottom dwellers. Introducing nudibranchs, a natural predator of the nettle’s polyps, was not effective.

Some scientists attributed the increased numbers of this sea nettle in the bay, and to some extent on the southeast Atlantic coast, to urban and agricultural runoff causing a nutrient overload. This causes an explosive growth of phytoplankton such as bacteria, protozoans, and rotifers that thrive on the nutrients. Since the sea nettles prefer these foods to higher forms of zooplankton, their numbers increase.

Blue blubber (Catostylus mosaicus)